Hello beloved patients, friends, and colleagues,

Happy Halloween! How is it nearly November?

As we head into the fall holidays, it is tragic to see so much pain and loss. It really breaks my heart Even though it feels like the world has gone crazy, I hope that we can all find ways to come together again. One way we can try is through communication.

In this month’s newsletter, I explain how hearing is different than listening. I also talk a little about Broadway history. Did you know there used to be nearly 100 theaters? And follow my breastfeeding blog.

Love,

Dr. Dahl

In ENT News:

The Difference Between Hearing and Listening

Working in New York City, I see a lot of patients who think they have hearing loss. They can’t hear conversations at business dinners. They have to ask people to repeat themselves at parties. They struggle to hear phone calls when they are walking down the street. These aren’t necessarily older people, by the way. Most of them are young and healthy with no history of hearing loss.

Last week, one such patient came in at her husband’s request.

“He keeps complaining he has to yell from the other room to get my attention. Why can’t I hear him?” she asked.

“Because you are married,” I joked.

She didn’t laugh.

“Let me take a look,” I said, proceeding to do what I normally do, which is first check for earwax. Much to my disappointment, there was no sticky glob to remove that would magically restore her hearing. So I looked for other possibilities, like fluid in her middle ear, an external ear infection, or exostoses, which are bony growths in the ear canal that happen from swimming in cold waters. I also made her try to pop her ear so I could check that her eardrum was moving. Everything looked good.

Next, I gave her a hearing test. It too was normal.

“So what’s going on?” she asked.

You’re probably wondering the same thing.

Here’s a lesson on how hearing works.

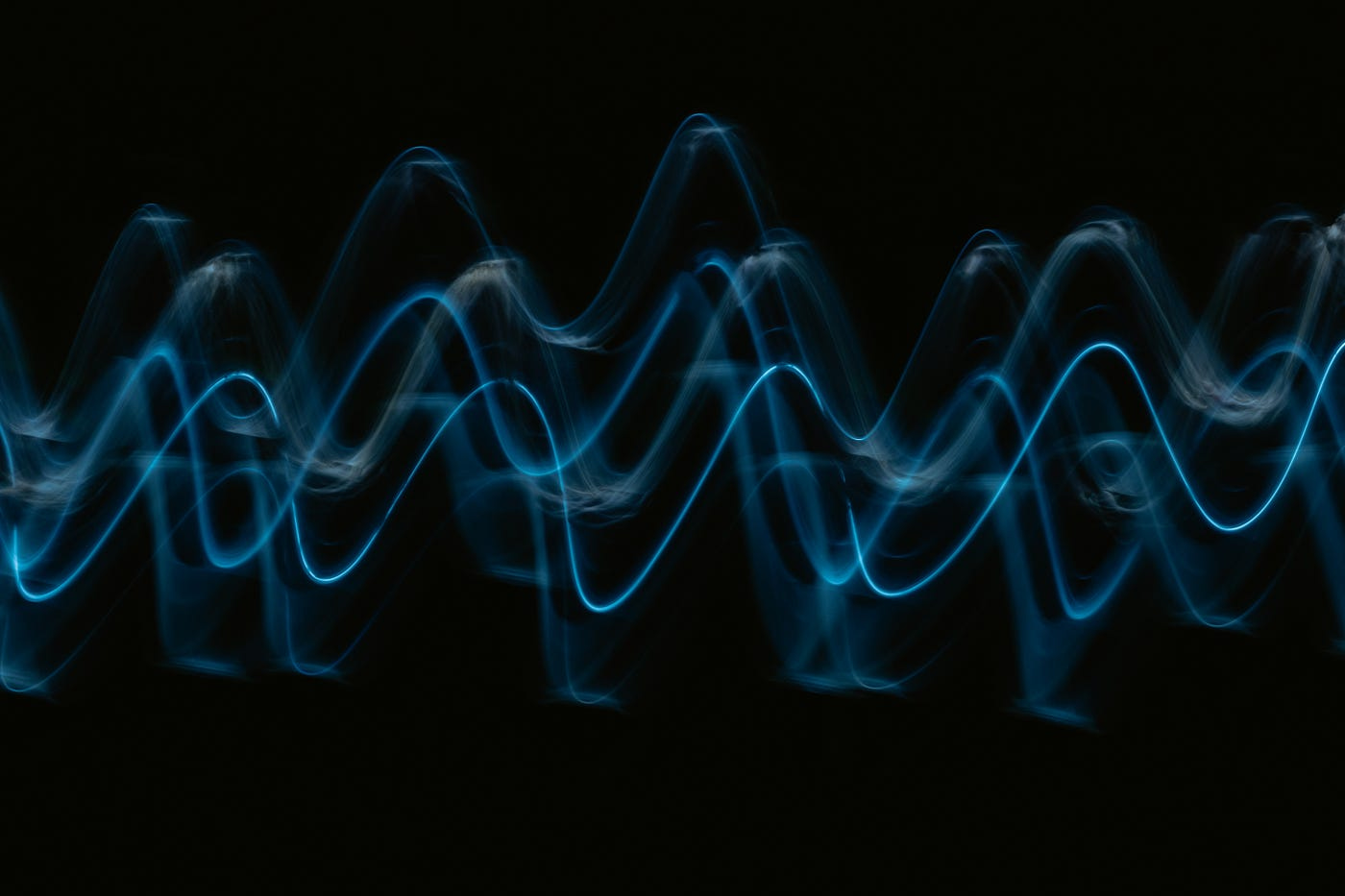

Sound travels through the air in waves, like in the picture above. When sound gets to your ear, it makes your eardrum vibrate at the same frequency as the sound wave. High-pitched sounds cause a fast vibration (think Mariah Carey’s whistle tones) and low-pitched sounds cause a slow vibration (think Barry White’s everything tones).

On the other side of the eardrum, inside the middle ear, there are three tiny ear bones called ossicles. Their Latin names are malleus, incus, and stapes, but I prefer their common names–hammer, anvil, and stirrup–because they sound like something Thor would use. These ear bones make a “chain,” connecting the eardrum to the hearing organ, or cochlea. When the eardrum vibrates, the chain of tiny bones also vibrates, which then vibrates a part of the cochlea called the round window.

There is no easy way to explain the cochlea because it’s not a simple organ, but here are the basics. The cochlea is spiral-shaped, like a snail, and filled with fluid. Along its inside edges, suspended in a bath of fluid, are tiny hair cells. These hair cells connect to the auditory or hearing nerve, which goes to your brain. On the wider end of the spiral, facing the middle ear, is a membrane that seals in the fluid. This wider end is called the round window.

When a sound wave is transmitted through the chain of tiny ear bones to the round window, it has kind of the same effect as a drum, causing the fluid in the cochlea to vibrate. This vibration makes the hair cells wiggle. Each hair cell wiggles for a specific frequency, like dancers in a 1970s variety show, based on its distance from the round window. Longer, lower frequency sound waves make the hair cells farther inside the cochlea wiggle. All that wiggling stimulates the auditory nerve, which then transmits those signals to the brain. Our brain then has to make sense of all that noise.

Putting it all together

You’re excited about the 20th Anniversary of Wicked on Broadway, so you flip through Youtube and find this incredible video of Jessica Vosk singing Defying Gravity. The sound waves float into your ears and vibrate your eardrum. That, in turn, makes Thor’s tools vibrate, and, since they are connected to the round window, they send that vibration to the fluid inside the cochlea. The vibrating fluid wiggles your tiny hair cells, which activates the hearing nerve. The hearing nerve then sends a signal to your brain, which makes you swoon and maybe even listen to the whole video again, because, I mean, the pipes on this lady!

This is how normal hearing works. Sound goes in, ear transmits the sound to the brain, and the brain processes the sound. Anything that gets in the way of this circuit can make it harder for you to hear.

But hearing is not the same as listening.

It’s easy to think that your brain notices everything you hear, but it’s not that simple. Your ears are constantly getting bombarded by sounds, from the low hum of traffic to the screeching of brakes on train tracks. Since your ears aren’t filtering the sounds (unless you are a smarty pants who wears noise-cancelling ear buds or your ears are plugged with wax), your brain has to decide which sounds are important and which ones to ignore.

The part of your brain where this deciding happens is called the auditory cortex, or hearing central. Even though a particular sound comes in, you may or may not perceive it if your auditory cortex decides otherwise. In other words, even if a sound gets through your ears with normal hearing, you won’t “listen” unless your brain tells you to.

Back to Jessica.

Imagine you are sitting in a quiet room trying to write an article about how hearing works, when your teenager’s phone rings. Her ringtone is the chorus of Jessica singing Nobody’s Side from the musical Chess–your daughter is a huge Broadway fan. The loud sound makes you jump up and burst into song because, in a split second, it got from your ear to your brain and back to your body, startling you out of your writer’s block. You are clearly not going to be able to work from home today.

Annoyed with your teenager and her intrusive phone, you decide to do your writing in a busy midtown coffee shop. Outside, an ambulance siren wails by. Gridlocked cars honk through a green light. The person sitting next to you spills juicy details to his friend about his disastrous date the night before, but you barely notice. Then a patron walks by and her phone goes off with a ringtone of Jessica singing What Baking Can Do–Jessica is very popular. Even though you love that song, you are so focussed on explaining the cochlea, you hardly look up.

Your brain is getting bombarded by many different sounds, but your auditory cortex filters through them and decides which ones are important enough for you to listen to. In this case, you don’t listen to any of them, because you are almost done with your article.

Now, imagine there is noise everywhere you go. (If you live in New York, you don’t have to imagine it. You just have to live here.) There is so much background noise, your brain often spends more time filtering than listening. To make things even more complicated, most background noises are high frequency sounds. Consonants are also high frequency sounds. Since consonants are how we understand language in English, it’s easy to see why it’s harder to understand what someone is saying when they are in a noisy environment. No wonder you can’t hear the guy across the table at Avra. All those high-frequency sounds blend together.

Fast forward a few years. After spending so much time filtering, your brain has gone into survival mode. Even back in your quiet room, you don’t notice louder sounds, like when your husband calls you from the next room. He starts complaining that you never seem to “hear” him these days and suggests you get your hearing checked. So you go to your doctor and get a hearing test. It is normal.

You can hear, but you aren’t listening. And now, you know why.

If you’d like to read more of my articles, you can access my Medium page here. You can become a Medium member here.

In Broadway News:

Did you know…

There are currently 41 theaters in New York that are considered “Broadway Theaters”. In the early/mid 1900s, there were ninety. Before that there were even more, with nearly two hundred show openings a year in the early 1900s. Back then, the Theater District was centered around the area that is now Union Square. But when real estate uptown became cheaper, the theater district was moved to its current location in Times Square.

Over time, many of those early theaters were repurposed or destroyed. And other theaters were built in different parts of town, like the Apollo Theater in Harlem and Radio City Music Hall near Rockefeller Center. But not all theaters can call themselves “Broadway Theaters.” There are strict guidelines that come with that title.

Interestingly, only three of the 41 Broadway theaters are actually located on Broadway (the Palace Theatre, and the Winter Garden Theatre). To carry the Broadway name, a theater must have 500 or more seats. It must also have a specific kind of contract that makes it part of the Broadway League, an association of theater owners and operators, producers, presenters, and general managers in North American cities, as well as suppliers of goods and services to the commercial theatre industry.

No matter their location, theaters with less than 500 seats are considered “Off-Broadway.” Currently, there are 19 for-profit Off-Broadway theaters and 30 non-profit theaters.

In Breastfeeding News:

Check out the Better Breastfeeding website and subscribe to the Better Breastfeeding newsletter! New articles are published throughout the month.

This month read about why babies sometimes choose the bottle over mom.

You can also follow us on social media:

Meta/IG: @betterbreastfeedingnow

TikTok: @betterbreastfeedingnow

To Make an Appointment:

EMAIL: info@drlindadahl.com

CALL 212-920-3047

We are available by phone Monday through Friday.

Did you know we also offer IV therapy? Speak to our staff about scheduling and pricing.

Office hours:

Tuesdays, Wednesdays, and Thursdays, 9 am to 5 pm

Office location:

535 5th Avenue, 32nd Floor, NY, NY 10017

(entrance is on 44th Street between Madison Ave and 5th Ave)